National Biography Award nomination

‘I am doing an honest action’

|

|

|

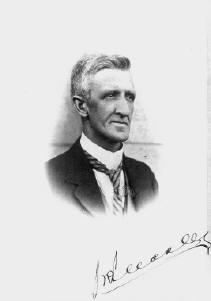

Leandro Illin Courtesy of the Illin family |

These stories survived in the Illin family for eighty years as an oral tradition and a historian might suspect that facts have been distorted during that period. I, however, am one who inclines to value the family tales no less than the facts. Luckily, during my visit to Townsville in 1996 and interviews with the Illins, Ernie, Flora’s son, received a long-awaited bundle of documents from the Department of Family Services and Aboriginal and Islander Affairs regarding Leandro and Kitty’s marriage. That provides us with a unique opportunity to compare how archival documents and oral tradition reflect the same events. Let’s listen to the documents. The first in the file was Leandro’s letter.

March 1915

To the Chief Protector of Aboriginals

c/o Mr A.A. Pike, Constable of Police, Yungaburra

Sir,

It is a difficult thing to write to you but a man must do it when it is necessary. I desire to obtain a permit to marry an aboriginal woman who’s name is Kitty Clarke. I know her for the last four years. She used to work occasionally for my mother.

She is a kind sort of a woman and reared by whites. She belongs to one of those tribes which counted hundreds one time at the present time being reduced to a handful. My selection is right in her country. I hope after inquires made about me you will not deny that permission. I would like to go and speak to you personally but it is so far to Brisbane and expensive and again there is such a lot to do. ...

The blacks are a poor starving lot and you will do her a good turn by giving the asked permission. I could write to you plenty more but it is hardly necessary. Regarding myself I do not drink, smoke nor gamble. ... Some people advised me not to write to you but I thought different as your qualification speaks to me that you work for the best of the blacks and you could not protect Kitty in a better way. It would be a very sorrowful thing if some evil happened to her in form of being taken away from her native country. I do not know the laws of this country but thinking I am doing an honest action. I hope you will understand me and give me justice.

I have honour Sir to remain your obedient servant

Leandro Illin

Peeramon. Gadgarra. Via Cairns NQ

Note: If you thought it would be necessary to come to Brisbane I would try to raise the necessary sum, though extra expenses for a starting man on the land is a difficult thing. L.I.

The letter was accompanied by a note from the Yungaburra constable, Alfred Arthur Pike.

27 March 1915. ... Both parties are well known to me personally and Illin bears a very good character.

The aboriginal is a full blooded Russell River black and she has three black picaninnies, she is an intelligent woman as far as blacks go.

I am of opinion that Illin would be well advised to wait six months as so to insure whether he will still be of the same mind as the blacks here are not adapted to civilized living and Illin would be courting trouble.

On 29 March 1915 the Atherton Protector, George Sutton, added his opinion to the note: ‘I have known this applicant for last six month, a very hard working man, I do not know of any objection to him marrying this gin.’

Ten days later the Chief Protector of Aboriginals, John William Bleakley, in Brisbane wrote his resolution on the same note.

I am very much averse to the marriage of fullblood aboriginal women to white men and especially where as in this case the woman has three aboriginal picaninnies. Return Illin his documents and please advise him I cannot grant his request. Perhaps it would be wiser to remove the woman and picaninnies to a reserve. 9.4.15.

Twenty days later he returned to the note once again, scribbling in the bottom corner:

Ask [Atherton] P[rotector of] A[boriginals] again if he considers it would be wiser to remove the woman and children, more secure. 29.4.15.

Thus, on the corner of a striped sheet of paper, a human destiny was cold-bloodedly decided.

|

|

|

John William Bleakley, NAA |

John William Bleakley — that was he, the evil hero Blakely from Harry Illin’s story. Born in 1879, he was nearly the same age as Leandro. One was the son of a Russian intellectual nobleman; he was a man who by his thirties had not achieved anything except hard toil on his block of land but for whom democracy and honesty in relation to all people was the only possible way in life. The other was the son of an Australian boilermaker, whose career — public servant in 1899, Chief Protector in 1914 — symbolised the Australian democracy, though he himself was far from being a democrat in the deep meaning of that word. The Russian poet Konstantin Balmont, who visited the Australian colonies in 1912, dwelt on this contradiction in the English attitudes:

‘The English exterminated the beautiful, dark-complexioned Tasmanian tribes and no trace of them remains. The savagery of the English exceeded even that of the Spaniards in their subjugation of the last Mexicans. The creators of political freedom were unable to comprehend simple human freedom.’40

Bleakley’s positive role in Aboriginal issues was recognised by his contemporaries and, moreover, he ‘was considered a liberal in his day’:

‘By the late 1920s Bleakley was a well-known Australia-wide voice upon Aboriginal welfare. ... His professional knowledge was built on common sense, hard work and accumulated experience, not on a liberal education and training in social anthropology or native administration. Although he was affectionately remembered by both black and white for his compassion, his approach was nevertheless rigidly parochial and paternalistic. His fervent advocacy of segregation, his long-standing preoccupation with “the half-caste problem” ... and his persistent theorizing on “breed”, “blood” and “race purity” show his acceptance of current racial ideas, since discredited. ... Bleakley’s energetic administration encouraged greater expenditure on Aboriginal affairs in Queensland than elsewhere in Australia.’41

It is a historian’s duty to give a balanced portrait of this personality but, for me, all his contributions to Aboriginal welfare in general will never outweigh the suffering to which he was planning to condemn Kitty and her children, and which was, at his behest, experienced by hundreds and hundreds of others, whose stories no one will ever tell.

Meanwhile, Bleakley continued to insist on his ‘advice’, this time on an official form.

5th May, 1915. To the Protector of Aboriginals, Atherton. In further reference to the aboriginal gin Kitty Clarke, for whom a permit to marry the naturalized Russian subject, Leandro Illin, was refused, please advise me if you consider it would be wiser in view of the refusal, to remove this woman and her children to a Reserve.

After the third reminder the Atherton Protector, George Sutton, who, it seems, did not undertake any actions in relation to Kitty, followed the ‘advice’ from above:

12 May 1915. [To] the Chief Protector of Aboriginals. With reference to aboriginal gin Kitty Clarke and her three children. I think it would be wiser to remove them to a mission. George Sutton.

The ball began to roll. Bleakley immediately sent Sutton’s memorandum to the Home Department with a note: ‘Removal to Hull River recommended’. In a few days the removal was approved and on 24 May 1915 the ‘Order for Removal of Aboriginals’ was issued in accordance with the Aborigines Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Acts.

To all Officers and Constables of Police, Prison Officers, and others whom it may concern. ... Now therefore, I, the Honourable Kenneth McDonald Grant [Deputy] Home Secretary of the State of Queensland, the Minister administering the abovementioned Acts, do hereby order that the four Aboriginals hereinafter named be removed from Yungaburra in the District of Cairns to the Reserve at Hull River for the causes stated in connection with their Names respectively … .

|

No. |

Name |

Offence, and cause for removal |

|

1. |

Kitty Clarke |

For her own benefit |

|

2, 3, 4. |

her three children |

To accompany their mother |

The law was scrupulously observed; Leandro’s appeal — ‘It would be a very sorrowful thing if some evil happened to her in form of being taken away from her native country. I do not know the laws of this country but thinking I am doing an honest action’ — was duly filed away.

Meanwhile, the tragedy of ‘a gin’ with three nameless children did not worry anybody: the removal was ‘for her own benefit’. No — there was one thing about her that did worry Bleakley. The order for removal was accompanied by his memo to the Atherton Protector:

26th May, 1915. ... Will you please see that when removed this woman takes with her the blankets which she may have received and any other clothing which she may possess at the time the Order is executed?

Suddenly, this huge, well-functioning machinery of state fell out of step, stopped by a lonely fighter, an obscure poor Russian settler from the far north:

12 July 1915. Herberton. [Urgent wire to] W. Gillies M.L.A. Parliament B[risba]ne.

I applied chief protector aboriginals for permit marry mother of my halfcast child through yungaburra police never got reply police chasing the woman sent new application who should not I take care of my child and his mother can’t stand see him taken to mission kindly see protector and in debt for life yours truly reply paid Leandro Illin.

The ball now began to roll in the opposite direction. David Bowman, Home Secretary in the newly formed Labor government, wrote a minute on the wire: ‘Get Home Sec[retary’s Dept] suspend order for removal and [get] fresh police report. Suspend further execution of removal order and obtain fresh report. D.B. 14/7/15.’

William Neil Gillies (1868–1928) and David Bowman (1860–1916) were two men to whom Leandro was grateful all his life and he passed on this gratitude to his children. They both were members of the Labor Party and came to politics from working backgrounds — Gillies was a farmer and Bowman a bootmaker. Gillies had owned a block of land in Atherton since 1910 and won the seat of Eacham for Labor in the Queensland parliament in 1912. For several years he was minister for Agriculture; in February 1925 he became premier but resigned in October of the same year, after his administration failed to efficiently handle industrial unrest. He was remembered by contemporaries for his personal kindness and considered a fair man. Bowman was one of the founders of the Queensland Labor movement in the early 1890s. In 1907 he became leader of the Labor party in Opposition. When Labor won the State elections in May 1915, he was appointed Home Secretary but died soon afterwards. He was a man of high humanitarian ideals and, according to contemporaries, ‘he had a powerful voice and a stout heart, and what he lacked in polished diction he made up in earnest vigour’.42

Following Bowman’s resolution, Bleakley had to send a wire to the Atherton Protector:

Removal order Kitty and three children Yungaburra to Hull River now suspended by authority Home Secretary[.] Please wire if Leandro Illin is father of half caste child of Kitty. 14/7/1915

Sutton wired the answer on the following day: ‘Your wire fourteenth Leandro Illin now Babinda near Cairns supposed Kitty and children with him.’

Meanwhile, the Chief Protector’s office had to send explanations to Brisbane solicitors Foxton, Hobbs & Macnish, who opened the case in defence of Leandro’s application to marry. On 17 July 1915 Sutton sent a new wire stating, ‘Leandro Illin now back at Yungaburra [with] Kitty and children’.

Finally, on 7 August 1915, the Yungaburra constable, A.A. Pike, recorded Leandro’s statement, attempting to put Leandro’s live language into a dry police document.

‘Leandro Illin states: I am a naturalized British subject of Russian parents. I was born in Russia.

I know an aboriginal female named Kitty Clarke who was signed on to work for my mother last year at Gadgarra.

‘Kitty Clarke gave birth to a half-caste aboriginal boy last July 4th twelve months [ago] of which I am the father. I have since kept the child myself and the mother sees the child daily. I give the mother food too. I take the food into the scrub and meet the aboriginal and provide food for herself and her four children. There are three children beside the half-caste belonging to Kitty.

‘The aboriginal is camped about two miles away from my house in the scrub.

‘I have kept the child at my house in the scrub all the time and the mother has been to Babinda Herberton and running away from the Police all the time to prevent her being sent to a Mission.

‘I have applied to marry Kitty Clarke and I am still willing to marry Kitty Clarke and keep her four children.

‘I will not say I have kept Kitty Clarke on my place.

‘When I had connection with Kitty Clarke I was in the scrub and it was not at my place or on my father’s place.

‘I think the best thing would be for me to marry Kitty Clarke and keep her.

‘Kitty Clarke I believe is in the family way, in fact I am sure of it. I believe she is to have another child to me. She may be five or six months in family now. Leandro Illin.’

Obviously, Leandro denied that Kitty lived in his hut because, until they were married, that was against the law.

Leandro’s statement was accompanied by Pike’s own report.

‘11 August 1915. ... I attach statement from Illin who was very averse to giving me any information on this matter as he was under the impression I was trying to get a chance on prosecuting him on his admissions for unlawfully permitting the Gin on his premises. His impressions were certainly correct but I could not get the necessary admissions. Though he had had the aboriginal repeatedly about his place I have not been successful in catching her on the place, it being in the midst of the scrub and a considerable way from Yungaburra.

‘Leandro Illin is the father of Kitty Clarke’s half caste child aged eleven months. He also states he is father of Kitty Clarke’s unborn child, though I think there is some doubt [if] he is the father or one of the blacks is the father. [Pike could not help trying to blacken in some way Leandro and Kitty’s relationship.]

‘The main point of Illin’s grievance seems to be the child of his and also the unborn child which Illin thinks is his.

‘If Illin was permitted to marry the Gin Kitty, he would keep these children as well as three other full blooded children of Kitty’s. As long as this aboriginal is in this part there will be trouble, and as Illin is as bad as the Gin I would recommend he be allowed to marry her. If permission is refused Illin will be in trouble over the children and he threatens to shoot himself and the Gin too, so that I do not see what should prevent him marrying her if he wants to.

‘Kitty Clarke is a sensible stamp of aboriginal and as his Russian neighbours state she is good enough for him.

‘I think the aboriginal would be well cared for if allowed to marry Illin, in fact she would be much better off than running in the bush, the loss would seem to be on Illin’s side and as he intends to marry her I think now he has two children to her it would be a fair thing if he did marry her, and I do not see the good got by send the aboriginal to Hull River.

‘Neither Illin or Kitty Clarke have given me trouble before and both were apparently well behaved previously.’

On 24 August 1915 David Bowman, the Home Secretary, noted on the report: ‘Under the circumstances disclosed by these reports allow the marriage to take place’.

We can imagine how unwillingly, two days later, on 26 August 1915, Bleakley had to put his instructions on the same sheet of paper, below Bowman’s resolution:

1 Permit to P[rotector of] A[borigines] Atherton.

2 inform W. Gillies.

3 inform Comm[issioner of] Police of decision and that such cancels order for removal.

On the next day the Office of Chief Protector sent a ‘permit to marry’ to the Protector in Atherton, who in his turn asked constable Pike to deliver it to Leandro. In the meantime Bleakley had to send the letter with explanations to Gillies.

31st August, 1915

Sir,

With reference to your interview with the Deputy Chief Protector of Aboriginals in July last in regard to the application by Leandro Illin of Yungaburra to marry the aboriginal woman Kitty Clarke I have now to advise that the necessary permit for the marriage was forwarded to the Protector of Aboriginals Atherton on 27th inst.

Yours obediently,

Chief Protector of Aboriginals.

This letter makes clear the first-hand interference by Gillies into Leandro’s case, which he kept under his personal control.

On 7 September 1915 constable Pike reported that he handed Leandro the ‘Permit to marry the Gin Kitty’. A week later Protector of Aboriginals of Innisfail reported, with some amazement, to the Chief Protector:

14th September, 1915. Sir, Re marriage of Kitty Clarke (Abo) to Leondra Albin. A Greek or Southern Europe alien came to-day to Innisfail from Russell River way accompanied by a female Aboriginal woman named Kitty and had a permit ... to marry Kitty. They were married at Innisfail to-day by William Simpson, Esquire, a Justice of the Peace who is authorised to celebrate marriages.43

Leandro signed the marriage certificate, Kitty put a cross.44 Returning to Gadgarra, they settled at Leandro’s. In a month their daughter Flora was born.

* * *

Comparing the events as they survived in the memory of Leandro and Kitty’s descendants and the documents from the archival file, we discover a number of discrepancies but mostly the facts complement each other. According to Flora’s story, after the police attempted to remove Kitty with Leandro’s son to Palm Island, Leandro made his decision to marry her and began the struggle. According to the documents it was Leandro’s application to marry Kitty which provoked the order for removal. Still, I do not exclude the possibility that Leandro and Kitty were aware of a threat of her removal after their first son was born. According to the documents, he wanted to marry Kitty to be honest to a woman who had a child by him — ‘I am doing an honest action’. Flora’s explanation — ‘I’ll marry the mother and save my son’ — seems not so idealistic but more worldly and understandable.

The belief that police intended to send Kitty to Palm Island (although in reality the order for removal was to Hull River mission, obviously Kitty could not know that) was due to widespread fear among the local Aborigines, who regarded Palm Island ‘as the ultimate hell’.45 Thus, the symbolic meaning of Palm Island gave Flora’s story an added dimension, making it more impressive than if it had been Hull River mission, which lacks this symbolic content.

The most dramatic episodes of the story, when Leandro hid with Kitty in the scrub ‘like a bushranger’ for several months and approached Gillies during his visit to Atherton, are not reflected by the documents at all. We could assume that this dramatisation had emerged as a later embellishment. Moreover, it was traditional in Aboriginal love culture for lovers, whose marriage was prohibited by the existing law, to run away to the bush and stay there until the conflict was settled. This ancient tradition might explain why this episode of Kitty and Leandro’s marriage became so popular among Kitty’s descendants. All these reservations about what was true might apply to other men but not to the Illins, who never hesitated to turn legend into everyday life. Leandro himself confirmed that the dramatic ‘bushranger episode’ did take place. In his later letter, of 27 April 1919, to the Home Secretary he wrote:

‘How I got married and why the Hon[ourable] W. N. Gillies could tell you as he helped me to do so after the Chief Protector Mr Bleakley refused to give me permit to marry and order[ed] Kitty (my wife now) to a Mission Station. Not wanting my children to be taken to a Mission I took to bush and had a very bad time of it. And only for the Hon[ourable] W. N. Gillies and the late Hon[ourable] D. Bowman I probably would had a sad end as I never would surrender my children to a mission.’46

Obviously, the intervention by Gillies into Leandro’s case was not provoked just by the cable Leandro sent him (cited above); moreover, Gillies kept the case under his personal control till it was successfully concluded. Indeed, the local newspaper confirms that Gillies did visit Atherton on 28 June 1915 (two weeks prior to his intervention into Leandro’s case) and that he, together with a deputation of local residents, awaited on the platform the arrival of the minister for railways with a request for a branch line from Peeramon to the Boonjie goldfield.47 This might be the moment when Leandro applied for his help. The fact that Leandro’s descendants have elevated Gillies to the rank of premier (in 1915 he was a member of the Legislative Assembly, only becoming premier briefly in 1925) simply reflects the laws of the creation of a fairy-tale, when the good master should have the highest rank.

Harry’s story about Kitty and Leandro’s dramatic flight along the Russell River to Innisfail to marry might seem, at first glance, hyperbole for we know that by this time Leandro had the permit to marry. Still, in the report of the Innisfail Protector there is one reference — an ‘alien came today to Innisfail from Russell River way accompanied by a female Aboriginal woman’ — which suggests that the flight along Russell River did take place. Obviously, Leandro preferred not to go with the permit to a more accessible part of the country (such as Atherton or Tolga) because this area was under the control of the local police and of the Protector who had hunted Kitty for several months, a man whom Leandro had grounds not to trust. Formally, the order for Kitty’s removal to the mission was returned by local police to the Chief Protector’s Office only after they had been married.

Thus, archival documents state their truth, a supposedly objective truth, but the oral tradition, for all its inevitable distortions, has its own truth, too. The oral tradition makes an important contribution to the abundant but dry historical facts, by distinguishing, augmenting and preserving the most important points and thereby clarifying the whole story. If not for Flora and Harry, these facts would never be so memorable, would never have become part of the life of the younger generation.