National Biography Award nomination

‘Dick is a man that looks a fellow in the eyes straight’

|

|

|

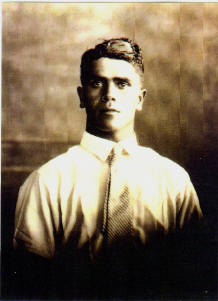

Richard Hoolihan, Courtesy of the Illin family |

Life, though, never allowed Leandro’s children to forget that they were Aborigines. The hardest battle they had to fight was for Flora’s boyfriend. He was Richard Hoolihan, also known as Dick Shaw, from the Valley of Lagoons station. They had become acquainted at Greenvale, where he had worked. His father, Michael Hoolahan (or Hoolihan), was Irish. His mother, Lucy, belonged to Gugu-Badhun. She was one of the wives of King Lava, who received a brass plate bearing this title from the whites. Richard, born in around 1905, grew up in the Valley of Lagoons absorbing what still remained from the Aboriginal culture of his ancestors. Years later anthropologist Peter Sutton would write about him: ‘Mr. Richard Hoolihan was my main informant, and the original instigator of the plan to have his language [Gugu-Badhun] recorded for posterity’.

But at the time when Richard met Flora posterity was the least of his worries. He dreamt of the world outside the station, about education. His Irish father had wanted to take him away from the station and send him to school, but Richard, because was ‘a half-caste’, was not allowed to leave the station. Leandro Illin was his first teacher. Richard would tell Ernie and Maud how ‘Daddy Illin’ showed him the letters and helped to write his first name. The rest he picked up himself looking at comics. Richard married Flora in 1932, soon after they settled at Stone River. Leandro helped him to obtain exemption from the Act. Flora tells the story.

|

|

|

Flora Hoolihan, Courtesy of the Illin family |

‘My father got a solicitor to get an exemption for Richard. They gave him an exemption from the Act, but they would not release his money. He had around £200 and police kept this money and did not give it to him. After Richard married me my father wanted to help him but police reckoned that my father was going to rob him for the money. In 1933 Queensland Premier Hanlon was coming to Ingham. My father took Richard and me and Ernie, he was just six months old, and my husband’s solicitor, and we all went to the railway station when the premier was arriving. The solicitor went to the police and said, “This man here wants to speak to the premier”, and the police went to the premier and said, “This man here wants to speak to you”. And the premier looked at my father and he said, “And who the hell is he?” And my father said straightaway, “Well, if you listen to me you will know who I am”. So he started listening. My father put us in front of the premier and he said, “Look, this is my son-in-law, this is my daughter married to him, this is my grandchild here”. He said, “They reckon they won’t release his money because, they reckon, I might take his money from him, rob him. What would I rob my daughter and grandchild for? It his money, they should release it for him.” After that, the premier promised that the money would be released and Richard got the money.’7

Flora’s story is a good example of traditional oral storytelling. It features a conflict between a hero and evil forces settled by a deux ex machina. It has a classical development with short introduction, rapid climax — ‘Who the hell is he?’ — and happy ending. The real development of the story as recorded in the documents was quite different in style: it was prolonged and exhausting, with human meanness, numerous features of the real life on the cattle stations and in police stations.

The file8 opens in 1925 when the owner of the Valley of Lagoons, L.O. Micklem, applied to the Chief Protector of Aboriginals to exempt Dick, ‘an intelligent boy, good rider and stockman’. Protector Hogan from Mt Garnet in an accompanying note asserted that Dick was unable to handle his money and was a ‘flash and loud half caste’. In 1928, working in Greenvale, Dick applied for the exemption for the second time, and again his application was followed by the report of the new Protector from Mt Garnet, J.D. Lucey: ‘The boy has defied the Protectors to place him under agreement and has also endeavoured to get other boys who are signed on at Gunnawarra and Cashmere Stations to refuse to work under an agreement’. It was rare indeed for such conscious civil disobedience to be practised by an Aborigine even at this stage in Australian history. Not surprisingly, he was refused exemption once again. But by this time the exemption had become an issue of extreme importance for him as there was Flora.

Leandro wrote about those days: ‘... he came to me and said: Old man, I want Flora! I said, it is no news to me! does she want you? She is alright! he said. And look here, he said, if she doubts me I will swim the Hinchinbrook Channel and get there or die in the attempt.’

Later, when they finally marry and Leandro is accused by the Ingham Protector of letting his daughter, ‘a mere child’, marry a ‘black fellow’ who was ‘totally incapable to look after himself’, Leandro wrote: ‘I thought the world of Dick and my daughter. The fact of him being a halfcaste did not prevent him to be an honourable man, a first class horsebreaker and an intelligent man who can read Tolstoy or London. ... As regards my daughter’s youth and her marriage she belonged to the Abo race who matured quicker and ... her mother (my wife) had her first child at 13.’ Leandro was not an obstacle to their marriage, by any means. The real obstacle was that Flora marrying a man ‘under the Act’ would herself then become a slave ‘under the Act’. Leandro remembered Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe, which he had read in his childhood. But even in a nightmare he could not have imagined then that the story might be repeated years later in a civilised, democratic country and affect his own family. He taught Dick spelling out of the book and it captivated both of them.

They lodged the third application for exemption and soon Lucey furnished the Chief Protector with a fresh report: ‘There is a Russian named Leandro Illen at Greenvale who lived with a gin some years ago, ... he would like to see Shaw [that is, Dick Hoolihan] exempt so as he could marry his daughter and use Shaws money to his Illens advantage’. After a new refusal Leandro, in despair, appealed for help to his old friend from the time of the 1912 Russian colony project, the Labor MLA, G.P. Barber, reminding him about their ‘long past meetings’. But even Barber’s intervention did not help. He was cynically informed by Chief Protector Bleakley, who artfully shifted the responsibility to the local Protector:

‘Although the man seems fairly intelligent and probably in other circumstances would be deemed capable of managing his own affairs, the Local Protector feels he cannot in the boy’s own interests recommend this freedom be given him at present. ... He also has a large sum of money to his credit and as the Russian, Leandro Illin is very anxious for Shaw to marry his daughter, it is felt that his persistency in applying for the latter’s exemption is not wholly disinterested.’

Barber’s support helped him, as Leandro wrote, to overcome ‘the insult and pain inflicted on me and my honour by the dirty Mt Garnet Police and the Chief Protector of Abos’. He later wrote to Barber: ‘I ... never a day in my life forget you and all you done for us’. Meanwhile, the nightmare continued. In 1931 the Mt Garnet Protector again reported that Dick ‘has tried to cause trouble with the other natives in this District by trying to obtain exemption for most of them, and if he were to be granted exemption now he would be more cocky than ever he was’.

At that stage the Illins had left Greenvale and settled in Utopia. To marry Flora, Dick finally submitted himself to work under the humiliating conditions of an agreement as an Aborigine, which he had not done since 1924. When Dick applied for exemption for the fourth time it was done from the Ingham area, out of reach of the Mt Garnet Protector’s accusations. It succeeded and finally, in February 1932, the Ingham Protector sent a favourable report to Bleakley: ‘He proved himself to be a good hard working boy and capable ... He never drinks and is very intelligent and honest.’ But Bleakley had a good memory and immediately reminded the Ingham Protector about ‘Illin, who is a Russian, lives amongst Aboriginals and was anxious to get Shaw’s money’. As a result Dick, although exempt on 4 April 1932, did not get his money, which remained in the hands of the local police. On 16 May 1932 Dick, now a free man, married Flora. But the happy ending was far away yet. Leandro wrote:

‘Dick ... was promised by the Protector to have his account released in 12 months. When he got married he decided to buy a runabout truck and applied for the money to the Protectors Office. ... £50 was granted. He did not wait, foolishly, in his excitement being married and borrowed £60 at 8 per cent of the friend of his childhood J.H. Atkinson. ... Himself an honourable man it never came to any doubt in his mind that his money will not be released and that the promise will not be kept. ... Then he applied through his solicitor for the release of his account and evidently the local police has objected and so Dick did not get neither the £50 nor his money. When he went with Solicitor Clements to the Police to try to meet P[romisory] N[ote] the Sergeant told him he will have nothing to do with it and that Dick can be put back under the Act. (Nice perspective for my daughter!).

‘I would not survive that. ... I am worried to death. I can’t sleep for worry! My daughter is pleading to Dick to write to the Protector and take all the money as it is the bone of contention. She says any half-castes that have no money live happy. Personally I am of the same opinion.’

By that time they had a newborn, Ernie, who might get into slavery together with his parents, too. After nineteen years of Leandro’s confrontation with the Chief Protector, Bleakley’s chance to teach ‘Russian Illin’ a lesson seemed to have come. Leandro realised that he could not lose a day. On 17 June 1933 he undertook the humiliating procedure of asking his neighbours and local authorities to sign a petition to the Home Secretary stating — as in a Kafkaesque nightmare — that ‘he is not a man to rob his family and son-in-law Dick Hoolihan. Leandro Illin is a very fond father of his children and son-in-law and dedicates his life fully to their welfare ...’ A few days later he, together with his family, confronted E.M. Hanlon, a newly appointed Labour Home Secretary, on the railway platform when the latter visited Ingham. Dick’s solicitor was to introduce them, but, Leandro tells, ‘went to pieces. ... I was not going to miss our chance and butted in’. The big boss did, indeed, promise to look into the matter but Leandro’s worries were far from ending.

A few days later, on the day of the Ingham Show, Leandro and his family confronted another politician, A.W. Fadden, MLA, a former resident of Stone River district. He was favourably impressed with Dick and promised them ‘hearty support’. Leandro recorded after the meeting: ‘During our conversation ... black and brindle lean to us. Although the Police calls them “halfcastes”, “black fellows”, Mr Fadden was not afraid to shake hands with them and even with my old cobbers blacks ... [and] was not afraid to talk to “low stupid black fellows” in front of all the town folk.’ That was the best characteristic for a politician in Leandro’s eyes and he began to trust Fadden.

There followed numerous letters from Leandro to Barber, Hanlon and Fadden — appalling human documents. Within one month, ‘half dead with flu’, he wrote at least fifty pages appealing for justice for Dick, for himself and for other Aborigines. He remarked in a letter to Fadden: ‘Writing such long letters might be annoying to you. It is like story writing and so it is, as it is pages out of a story of a man’s life.’

Dick Hoolihan was main hero of the letters. His car — a flashy second-hand ‘Pontiac’ — that caused all the trouble and which he bought in Townsville against the advice of Leandro, who was ‘an enemy of all cars’, broke down halfway from Townsville to Ingham and after numerous repairs Dick exchanged it for a more reliable Ford utility. Still, Leandro never reproached Dick, just stating that he ‘has learned his lesson about cars’. Leandro always treated Dick with love, respect and understanding. Describing Dick’s confrontation with the Ingham Protector, Sergeant Collier, Leandro wrote:

‘Dick is a man that looks a fellow in the eyes straight. ... Dick came and told me: “that Sergeant can’t look a man in the eyes. Every time I look at him he looks sideways or down.” By the way Dick is one of them inexplicable mysteries so often described in books about native races. He suddenly tells us sometimes about something is happening away somewhere. Telepathy is very developed in him. He often reads another fellow’s mind. He knows when there is a death anywhere about or someone coming. ... As a horsebreaker: the wildest of the horses start to shiver and stand still once he puts his hands on them and his face against their nostrils. ... He broke ... most of Atkinson and Alston’s blood race horses. And that is the man they try to keep at 30/- per week!’

Besides praising Dick’s numerous bush crafts, Leandro wrote of him in terms the like of which the Chief Protector’s Department had probably never heard before from anyone about an Aboriginal person. The department, he said, asks for:

‘references from men who can read only beer labels on bottles ... [for] men who read Tolstoy, Beecher Stowe, Jack London, [Richard] Dana and a host of others names of authors that most policemen never heard. There is more inside of Dick Hoolihan’s woolly head than inside of a dozen full blown Sergeants (sometimes beer blown). ... Dick is the only really sober, truthful, intelligent above the average, decent fellow in town I know of. And I would not have a paddock full of whites such as they are.’

The situation arising from Dick asking for his own money which nearly resulted in his being put back under the Act, dragging with him his wife and baby, put paid to Dick’s plan to apply for 8 acres on the bank of the Stone River; he wanted to build a hut there for his family, go in for poultry and be his own master. ‘Why can’t they help the emancipation of a man instead of keeping him down?’, Leandro appealed. ‘The Police if they are Protectors should not reproach a halfcaste being one. ... He is not guilty that a white man stepped into the shoes of the man who should have been his father.’

In these letters Leandro wrote about numerous cases when Aborigines were severely bashed by the Ingham police, which seemed to be a powerful institution — ‘I don’t want any inquiries as it is too dangerous. Once a man gets in the bad books with the Police he is a doomed man. He can be bashed about under the slightest pretext.’ Even so, Leandro always gave justice to honest people whom he occasionally met among policemen: ‘But I must say that every halfcaste gives a great name to Constable Lewis lock up keeper. He invariably according to their reports comes on the scene and intimidates that he does not want the boys bashed. He advises them paternally to keep sober, tells them he does not want them in the lock up, feeds them.’ Such paternalism was widespread. In Dick’s case, when Dick came to Sergeant McHugh asking for £1 for his wedding the Sergeant suddenly said: ‘Give him a fiver, ... a man wants more than a pound when he gets married’ (this being at a time when Dick had over £200 in his bank account — kind policemen, indeed!).

‘As for me! Am I not only one of the fathers of 3000 odd halfcastes in Queensland?’, Leandro wrote in a moment of despair in his letters to Hanlon and Fadden. ‘There is 3000 more halfcastes in Queensland that have fathers who neglected them. They are men in all walks of life. There is sons of squatters, station bookkeepers, stockmen, farmers, town residents and I know even halfcastes who claim policemen and clergymen for fathers. You can meet them every day. Well to do, comfortable, successful, married to white women. Most respectfull. I am one who would not leave my load allotted to me. I carried it in the face of the world. And I get all the kicks. ... For 19 years I done my duty to my family and I fought for every black that I seen wronged. ... The Chief Protector thinks me a crook and the Mt Garnet Police also Charters Towers have slurred me. They are protected by the Maltese Cross, and it is foolish of me ever to think I will break through that wall. ... Now my spirit is broke. I only want peace for mine.’

‘Better to break, my son, but never bend’ — the uncompromising injunction his father had placed on him when Leandro was just eight years old seemed to have come to pass. But there were people, his black brothers, for whom things were much worse than for him, and he, crushed and maligned, would rise again and again and continue to demand from the officials real protection and justice for Aborigines, however utopian that might seem in those harsh times:

‘Why the Hon. the Home Secretary does not form an Aboriginal Affairs Committee locally selected and let the blacks select a man or two black or white and report to the Chief Protector. Any sick, needy, down trodden fellows could approach them and be communicated through them to the Home Secretary’s office without being totally dependent on the over bearing unsympathetic insulting Police.’

Biased as I am in knowing what a crystal-clear, honest man Leandro was, I still make myself look at the situation through Bleakley’s eyes. His grandson, Neville Bleakley, says about him: ‘He was no power-broker. He was a quiet, dignified, bookish man who, as a public servant, wrote policies for the government of the day. He was benevolent, if very conservative. ... He honestly believed he was acting in the best interests of the Aboriginal people.’

And I ask myself — could it be that he honestly believed that Leandro married his daughter to Dick just to get hold of £200? Could he honestly believe that denying Dick’s exemption and making him work under the agreement, which halved his income, protects Dick’s interests? That no man would help Aboriginals disinterestedly, as Leandro claimed to do? It all might just have been possible if it were not for the fact that he had known Leandro since 1914, when he, one of thousands of white men, married the Aboriginal mother of his child, and parted forever with his own parents in order not to separate his wife and his stepson, and raised six children after his wife’s death ... I cannot find any reasonable explanation for Bleakley’s attitude. Probably he just shared the Ingham Protector, Sergeant Collier’s position: ‘An Aboriginal is an Aboriginal to me’. ‘To me he is a human being’, Leandro commented about these words. On the National Sorry Day Bleakley’s grandson said ‘Sorry’ on behalf of the grandfather he remembers.9 It is for Aborigines to decide whether or not to accept this apology.

As for Richard Hoolihan, the main character in this particular story — this first victory in defending his human rights, their win over the system, made a deep impact on the rest of his life. A relay in defending human dignity and equal rights that started with Nicholas Illin in the 1870s, passing the baton on through Leandro and his son-in-law Richard Hoolihan, reached Koiki Mabo in the 1960s, who by the 1990s turned the tide of Australian history.

Meanwhile, Leandro, a dreamer from Utopia, continued his struggle for equal rights for Aborigines. The case of his stepson Ginger (George Williamson) never stopped worrying him. A letter of 1940 to the director of Native Affairs signed by Ginger — Leandro taught him to write, too — was obviously composed and written by Leandro himself. Who else would put humiliation above financial injustice when writing to an official about an Aboriginal’s problems at that time!

‘It is very humiliating for George to receive a different rate of pay to what his brothers receive on the same sort of work. ... George is sufficiently enlightned and capable to manage his own affairs and knows very well right from wrong.

‘George is an able drover, horseman, timber cutter, lorry driver and general labourer.

‘His mother died in 1925 but he [sticks] to his brothers and sisters as well as to his stepfather and he knows no other home. It is an humiliating anomaly for him to be the only member of the [family] ‘under the Act’ and it hurts immensely his pride. His intelligence and his social outlook is in no way inferior to his brothers nor any average man. George is clean, temperant, courteous, ... very humorous and well behaved and well like[d] by all who know him well. George is no camp frequenter as camp life does not appeal to him. His social principles are very clean and sound (born in him).’

An Aborigine with a sense of humour and pride, with inborn ‘clean and sound social principles’ was an unusual idea for the authorities to deal with and it took them a year-and-a-half before George was granted complete exemption from the Act.10

Leandro’s fame as a defender of Aborigines went far beyond the Ingham area — to Valley of Lagoons and Greenvale, to Blue Waters and Christmas Creek. ‘He had a lot to do with a lot of Aborigines there’, Harry says. ‘They used to go to him for help because he was an educated man.’ Marnie Kennedy tells about Leandro in her book Born a Half-Caste:

‘Daddy Illin, as everyone called him, … fought for many Aborigines whenever they got into strife with the police and they went to him with their problems and it was through this grand old man we Aborigines learnt a lot. ...

‘One day I went with a few other Aborigines to get money (the police had control over money) and we waited all day. At five the police told them to come back the next day and that’s how it went on. So Daddy Illin would go to the police to find out the reason for the wait. By that night they would have their money.’

Ernie, Leandro’s eldest grandson, remembers those days, too.

‘When Aboriginals come to town, they had to go to the police station and ask for their money. It was their own money that they earned and yet they had to go and ask for it. And the policeman used to get them to sign a paper, many of them could not read or write. And some of them just put a thumb print for it. There was a lot of corruption went on. They were signing for £50 and only received half of it. Grandad Illin he travelled around that area Christmas Creek, Greenvale and got to know a lot of them. When they come to town they used to ask him to go up to the police station and see what they were signing for. And grandad Illin he used to help them ... These police, they used to try to talk over him and be smart with him or tell him off. They would tell him they would report him to people down south. They tried all sorts of things. They arrested uncle Tommy and uncle Dick one night, just as they were walking down street going home, and police came along and grabbed and arrested them, just for nothing. So grandad Illin went down to the police station and got them released straightaway as there was nothing.’

Flora put it into a nutshell: ‘They said all sorts of things about my father. Because he stuck up for the black people.’11

Soon I learnt that ‘the black people’ were not the only people that Leandro stuck up for.