National Biography Award nomination

‘My dark brother’

|

|

|

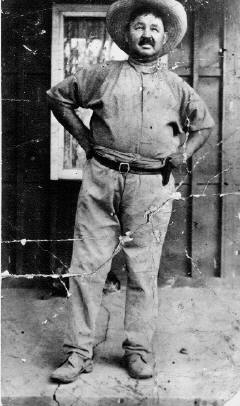

Leandro Illin, Greenvale Station ca 1927 Courtesy of the Illin family |

For Leandro, to be true to the memory of Kitty was to act, not just to grieve. And there was a vast field of action that awaited his attention, which was the practical defence of Kitty’s people. Working with Aborigines in Gunnawarra, Greenvale, and Christmas Creek, listening to their stories, driving cattle with them to Mt Helen, visiting local Protectors in Ingham and Townsville, he discovered the brutality of the system of so-called protection in all its details.

Kitty’s son Ginger (George) was one of the first whom he had to protect from the protection laws. And again he had to apply to Bleakley.

April 7th 1926

Greenvale

Clarke River

The Chief Protector of Aboriginals

Home Secretary’s Dept

Sir,

As you might remember ... in September 14th 1915 I have married an aboriginal woman Kitty Clark. On May 17th [1925] to my great sorrow she died giving birth to a little boy who was borned dead. She left me with one stepson and five children of my own.

It is about my stepson George that I am going to deal in this letter. I have reared the boy since August 1913. He was 14 years old on January, 1st last. Having reared the boy I am deeply attached to him and he is very affectionate to his brothers and sisters. My own boy Dick is 11 years old, then follows Flora 10 years old, Tommy 8 years, Harry 6, and Araluen 4 years. I have no other help. ... I am camped out now 16 miles from the station. My poor motherless children stick together and although I had offers to have some of them taken of[f] we try and stick together, my poor little girl looking after smaller ones.

Mr H. J. Atkinson suggested to me to let George to work in the camp. The boy is big enough to ride and do stock work and earn a little money for himself but I do not like him to be under agreement as if I leave the place and change employer he has to remain behind. Neither he nor I want to be separated for the sake of the other children.

Mr Atkinson proposes to give him pay and if I leave, the boy to leave with me. Now under the agreement this is rather difficult. Therefore I would like if you could do me and the kiddie a favour, that is: to allow him to work under permit to any employer where I work and live with his brothers and sisters without signing agreement for definite periods, all his wages to be paid either into his banking account or the local Protector.

I do not want the control of his money but I want to keep him and protect him (as his mother’s wish always was) from being ill-treated. Children of his age are generally whipped on the stockruns. They don’t dare to do it to him while he is under my protection.

I have reared him a good honest able boy, like his poor mother was, he is totally unspoiled, is reliable and smart.

If I loose control of him he might loose his honesty and be used as a tool as many boys on stations are.

Still my main reason to make this application is that I simply can’t part from him on account of the other kiddies whom he loves tenderly.

Some time ago (in January last) a man in my absence swore and threatened my little boy Harry six years old. He got frightened and cleared out bush. That was in the morning. The other children missed him but called in vain. He was gone. George went and found his tracks and followed them four miles and found him in the evening at a junction of Wyandotte and Spring Creeks and brought him home in the evening. So you see I can’t part with him.

I bank him a little money into the Saving Bank. I receive award wages £2 15s per week and get 15s per week toward the children’s keep. If George receives wages he can cloth himself and make it easier for me for the other children. I am putting a very hard battle since the wife died and if the boy was tied up by agreement it would be a lot harder for me and the other kids and George would not like to be left behind.

... Asking you once more to do me this favour for the sake of my poor motherless children I am yours faithfully Leandro Illin

Years after slavery had been abolished in the United States and serfdom in Russia, ‘democratic’ Australia continued to practise actual slavery in relation to its Aboriginal population (‘half-caste’ as well as ‘full-blood’, according to the terminology of the time). Under the Protection Act, Aborigines were obliged to enter into agreement with the whites to work for them from their teenage years. The employer had to pay wages into their bank account, which was administered by a local policeman. This seemed fair enough to the European onlooker, but the problem was that the Aboriginal often could not choose the employer and was forcibly allocated to one by the police and, after signing the agreement, an Aborigine could not change his employer for one year, however harsh conditions were. What happened with his earnings administered by police we will see further on. Leandro’s children after his legal marriage were exempted from this Act, but Ginger’s destiny, as soon as he reached his teenage years, was to become this kind of assigned slave. The battle for him was started by Leandro in 1926 and lasted till 1940.

Bleakley this time seemed to treat the case more favourably. But, while Mt Garnet and Ingham police and Protectors discussed in whose territory ‘godforsaken’ Greenvale was, Leandro, not receiving an answer, wrote a new, bitter appeal to Bleakley.

May 25 1926

... All my dealings with you were so far very hard ... The trouble is that although both of us [are] most well intentioned towards the Abos we look on things from a different point. You in your official capacity have to trust and depend in everything on the police. I mistrust the police and consider them as a body privileged to do harm to the Abos. A policeman can do and in most cases does what we simple mortals are fined for. ...

Now I am enclosing 3 photos for you to see my family. You will see that my plight is real and I need George (Ginger as we call him). Please, decide one way or the other. His Granny Emily Denyer also wants him. The boy needs nothing while he is with me. I am in great suspense.

I want two of the three photos returned marked thus +. On one of them is my late wife. I suppose you are waiting for the police report to decide on the matter. ... The police is sure to report to oblige a squatter not considering that I saved the boy from all troubles up to now and reared him. I know you are humane as you was decidedly so in Denyers case in Atherton and I think you will do this for me, for the boy and my family.

Finally, in June 1926, the case was decided in favour of George. Although not exempt from the Act, for the time being he was allowed not to separate from his family.14

Alas, other Aboriginal boys did not have fathers like Leandro, and this did not stop troubling him. A few months after Kitty’s death, in August 1925, the North Queensland Register published a letter to the Editor signed with a strange pen-name ‘Meekolo’. Reading it, I realised that there could hardly be anybody else except Leandro in northern Queensland at that time who would so passionately raise his voice in defence of ‘the son of this soil’ — the Aborigine. Later ‘Meekolo’ disclosed his pen-name and, indeed, he turned out to be Leandro. In that first appeal he wrote:

‘In the beginning the Abos were shot down like dogs or worse. Now that they are a dying out race the Government passes laws for their so called protection. The laws in some ways are all right but in most ways are all wrong and the trouble is that the injustice to the Abo is done not by the bushman nor other private individuals but mostly by members of the institution in whose hands the Abos are and who mostly are not Queenslanders at all but big men from overseas who largely invade that particular department. The Abo’s life is not his own but it belongs to his employer. He is lucky if he gets a rich employer who can afford to give him all he requires besides what is paid in to the hands of the police. ...

‘I know a boy15 with a family — a wife and three children — he has been working all his life under the one employer and has an account in the hands of the police for over £300 yet when he applied for a sum of money to buy a buggy, the protector did not grant it.

‘During eight months of last year I was down to a coastal town once every month [it was when Leandro drove cattle to Mt Helen]. The second trip I came down I went with an old boy16 to the police station to try to get some money for the boy. In August 1923, was the last time this boy was at the police station and withdrew £5. It was April 1924 when he went up with me and asked the sergeant for money. The sergeant told him “you got some money not long ago”. The boy said he did not. The sergeant said he did and that he would not give him any money. So I chipped in and knowing the exact day when the boy was down last I told him when it was and on looking through the books he said, “You are right, come later on”. When the boy returned he had a slip made for withdrawal of £3/13/10. I remonstrated that it was not enough for him. He wanted two flannel shirts, two pairs of trousers, hat, boots, blankets, etc. “That is all he gets”, was the gruff retort. Quite enough if he buys clothes just for himself, the Sergeant said. I could see through the policeman’s strategy. He was practically accusing me of trying to get the boy’s money so as to hurt my feelings and make me go away. ... The boy that got the above mentioned £3/13/10 had a credit account of over £164.’

On another occasion Leandro witnessed an even more dramatic scene which obviously reminded him of the lesson he was taught in the Northern Territory when a station owner demanded, ‘Don’t you spoil my blacks for me!’.

‘Once a sergeant of police was transacting savings bank business and had several books in his hands. He turned round to me and said, “This is not bad for an Aboriginal!” The amount showed £264 odd. I knew the boy and knew the district where he came from. I knew his old father to be starving on a creek. I told the sergeant about it and suggested that he should see the boy and give him some money to purchase tucker for this very old father. I knew the boy would be only too pleased to do it as they only looked with contempt on their money in the bank. They say always “police gets our money”. The sergeant on hearing my suggestion straightened himself to his six feet odd, brushed his beautiful long moustache and answered that he knew nothing about that. That the boy was a very good boy, that he never came to ask for any money and it was no use spoiling him. Then with a great dignified and hurt air he walked away holding hard a few passbooks in his hand.’

Furthermore, Leandro disclosed numerous cases when the police released some Aboriginal earnings but used the money to buy clothes for Aborigines on the stations without their consent — the clothes were of low quality bought at the highest prices and of ridiculous sizes. Otherwise, when the boys visited the town police directed them to buy goods in a particular shop. Leandro wrote about them as a concerned friend and father who recognises their human needs.

‘Spurs, saddles, whips are articles the police in most cases do not consider as necessary for them to buy; yet every boy loves to own these articles and the money they want to spend is their own. ... They all like musical instruments and little things that we all love yet they are deprived of all but what the protectors approve.’

But the main issue that worried Leandro was Aboriginal human rights — an idea unheard of at that time.

‘Boys sign on and once they do so, no matter what happens, they cannot break their agreements. Some boys are “signed on” without having seen the agreement, they neither been in the presence of the police to put their cross or anyone else. The usual thing is “the boss said I am signed on”. Every boy should be asked in the presence of J.P., besides the policeman, if he wants to sign on, or not. No Abo should be sent to a settlement on a report of a policeman alone, but should be tried publicly before he is deprived of his native land and liberty and deprived of his friends and relatives. ... To threaten boys with Palm Island to compel them to work for an employer they do not want to work for ... in my opinion is a total misapplication of the Protection Laws and against all the highest traditions of British freedom and liberty.

‘In the old days when there was no protection (so the old bushmen tell me) the squatters fed the camp as a whole. Bucks17, young gins were worked, the young, old and feeble were also provided and all were allowed to have a “walk about”. Now the destitute and feeble have got to go to a prison settlement. The young ones allowed to exist on the stations and be parted from their relatives. How would you, fellow workers, like to have your earnings confiscated and only allowed to draw money at the mercy of someone who does not know your needs or does not want to know them? ... We, white workers, are deducted 3d. per week for the unemployed. The Abo has 75 per cent of his money withheld from him.

‘I am an outsider and my interest in the question is only pity for my dark brother. I suggest that every district should have a honorary board for the Abos’ welfare and elevation, consisted of disinterested members with country members included.’18

Leandro’s ideas and attitudes were too greatly in advance of his time. The solutions he saw were ideas that have only recently been more generally adopted — he believed that the Aborigines should be treated as equals by the whites, should have the same rights enjoyed by all other Australians, and, moreover, he stressed the natural right of the Aborigines to stay on the land of their ancestors, together with their community. Equality, not corrupted paternalism: this was the attitude that Leandro manifested in his own life; this was the attitude which he demanded from official Australia. W.B. Sinclair, the only one who wrote to the newspaper in support of Leandro’s appeal, saw the solution of the problem quite differently from Leandro. ‘Segregation? Yes, and quickly’, he wrote, believing that the white men living with Aboriginal women and settlers exploiting Aborigines were the main evil.19 Sinclair was unable to look beyond that and to share Leandro’s concern that the arbitrariness of police and Protectors was no less dangerous than the harm caused by the pastoralists and farmers.

An Aboriginal bush-lawyer, Leandro was also a bush doctor for the Aborigines around the station. This is just one of the cases told by Flora.

‘Father always was friendly and stuck up for the black people. People on the station used to come to him, looking for things, whatever there was wrong, he was the doctor around the place, all the dark people and some of the white people would ask him, especially the dark people. He always did his best to look after the sick people, always had a lot of pity for sick people.

‘There was one old black fellow there and he was very sick, his legs were swollen and nobody worried about him, but my father was worrying about him. And luckily a doctor travelled through there. You could see that he was a doctor because those days if he was a lawyer, or a solicitor, or a doctor you could pick him [out] from the street. Father started talking to him and found out that he was a doctor. Father said, “Have a look at this fellow, why is he a sick man”, and this doctor got him, put this thing on, he had the things with him to test you, looked at his legs and said, “Yes, he’s very sick, he had dropsy, water gets into the blood”. Father told the station owner, “This man is sick, should get him to the hospital”. They sent him and he died later in Ingham hospital.’

Some years later, being accused that he ‘associated with blacks’, Leandro argued: ‘My associations with them have been in no way detrimental to the blacks and if I had now in cash what I spent buying Iodine, Boracic, Quinine, Aspros, Heenzo, Castor Oil and Epsom salts, bandages, ointments etc. I would have a goodly sum’.20

Mac Core, when he was a boy in the 1920s, knew Leandro. Now, remembering him, the first thing he said was: ‘He was very good to the younger Aboriginal people’.21 How proud Flora and Harry were to hear this acknowledgement of their father’s attitude.

There are numerous letters written by Leandro in defence of Aborigines stored in different files in the Queensland State Archives. Sometimes he wrote these letters at the request of an illiterate Aborigine; sometimes he fought alongside him, conveying facts to the Chief Protector or Home Secretary. ‘I fought for every black that I seen wronged’, Leandro would say about his position. They very seldom won; sometimes he would experience moments of despair but, still, he never gave up. He did not live to see the fruits of his struggle. But it was not in vain. Years would pass and his grandchildren — Ernest Hoolihan, Alec Illin, Glenda Illin and many others — put his ideas into practice, building a new society of equal opportunities for their own children and grandchildren — the Australians.